Author: Alexandra Rodríguez, Economic Development Agency, CONQUITO, Head of AGRUPAR

Gender justice and women’s empowerment are central to Quito’s participatory urban agriculture project, AGRUPAR, both as a means of food security and nutrition and as a final goal. This article provides insights into how gender-related data informs the project, the threats faced by women farmers, and next steps for gender transformative food interventions in Ecuador’s capital.

Empowering women to make life changes

Women in vulnerable situations represent 84% of participants in AGRUPAR, which provides the resources, knowledge, skills and opportunity to make positive life changes and to improve the health and well-being of their families and communities. Participants in AGRUPAR are trained in agroecology, farm animal husbandry, food processing and entrepreneurship.

All together, participants produce over 105 types of food, guaranteeing a diversified, healthy, local, fair and nutritious diet throughout the year, and reducing household food budgets.

AGRUPAR also breaks with convention of intending organic foods for consumers with high purchasing power or for export. It is the first national project to achieve organic certification for urban production, opening micro-business opportunities to small farmers, especially women heads of household who are unemployed, elderly, disabled, or victims of domestic violence, who are unemployed, elderly, disabled, or victims of domestic violence, who otherwise would be excluded from productive life.

Collecting and using gender data

The AGRUPAR project collects gender-differentiated information when a new participant registers and in the initial analysis of the productive unit, along with information on level of schooling, age and occupation. Women’s motivation for joining is also taken into account, as they might have several objectives: permanent access to healthy food, entrepreneurship, environmental education, occupational therapy, or recreation.

At each training and technical assistance event there is a gender count to determine the number of female and male beneficiaries, and the number of urban agriculture enterprises and self-employed women and men are also determined monthly. All the gender-related data allows us to plan appropriate interventions in terms of participant’s time, level of

education, investment capacity the garden, and opportunities for change.

The greatest threats facing women farmers

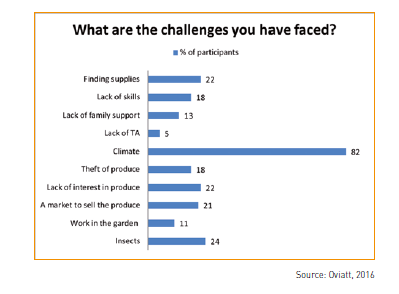

The most significant challenge facing urban producers is climate. In a 2016 survey of AGUPAR participants, 82% indicated that climatic events – such as hail, a number of consecutive dry days, excess rainfall in short periods, and frosts – have caused the most difficulties since they started their food garden. In terms of resilience, gender inequality and the multiple vulnerabilities faced by smallholder women farmers translate into a limited ability to cope with adversity.

A second threat is land ownership. Seventy five percent of women AGRUPAR participants said either they own the land themselves, or their husbands, or someone from their

immediate family. In theory this could give a degree of protection, but in practice family connection may not be enough to safeguard the land for food growing if another

use is proposed or if the couple separates. Twenty one percent women participants reported that the land they use does not belong to them.

Integrating the right to food and women’s rights

In Quito we are still promoting recognition of food within municipal planning as an important aspect of sustainability and resilience, but the right to food and women’s rights must be considered together and not as separate issues. It is important to recognise the role women play in food security and sovereignty, and to support not only indigenous women in rural areas but also urban women farmers who guarantee access to healthy food and improved incomes for households whose heads are unemployed or those facing extreme poverty and vulnerability.

Moreover, in Ecuador there is enough food to meet the needs of the population but the number of people affected by hunger and malnutrition continues to rise, with disproportionate effects for women and girls. The food needs of female family members are still neglected in the home, where discriminatory social and cultural norms persist.

This article was originally published in Urban Agriculture Magazine 37: Gender in Urban Food Systems. We’ll be posting more articles from the magazine throughout the week, so stay tuned.

Read about how Quito’s urban and peri-urban gardens are contributing to the COVID-19 response.