African cities need to develop active urban food systems governance systems at a pivotal moment in their development, according to experts at a recent AfriFOODlinks webinar. While some cities are making progress, common challenges remain –- including institutional barriers, lack of funding, and the risk that food systems can drop off the urban agenda following political change.

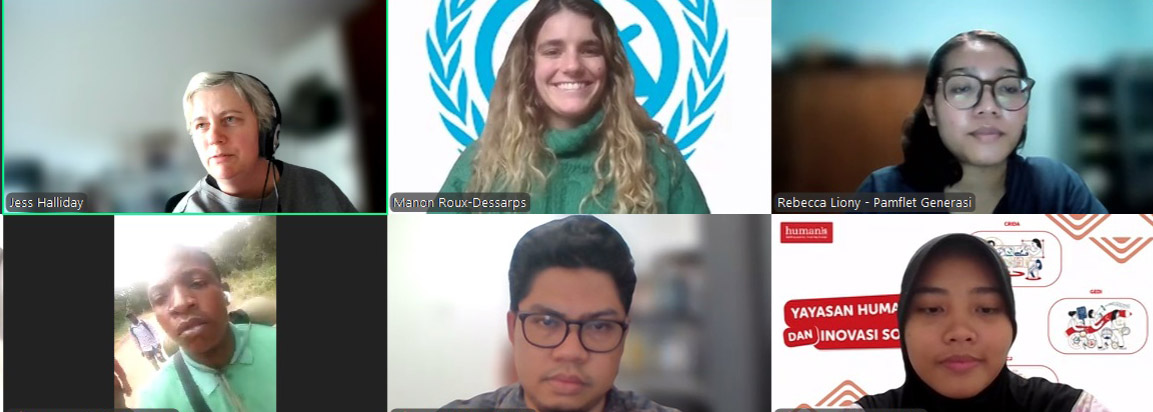

The webinar took place on 23rd January and was the second such event under the AfriFOODlinks Community of Practice for Transformation of Urban Food Systems, which links researchers and policy makers across Africa and Europe, promotes networking and shares knowledge on best practices on Urban Food Systems governance in Africa and beyond. It was organised by Hivos in partnership with the RUAF Global Partnership on Urban Agriculture and Food Systems.

The event was chaired by Michael Oloko, Professor in the Department of Agricultural Engineering and Energy Technology at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST).

Jess Halliday, Chief Executive of RUAF, set the scene by introducing key concepts and the importance of inclusive multistakeholder platforms. She was followed by Gareth Haysom, Senior Researcher, African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, who applied an African lens to urban food governance.

Haysom noted that African city governments tend to believe they have no food mandate – even though they do a lot of food-related work, such as managing urban markets, planning approvals for supermarkets, managing infrastructure, etc. However, in the context of rapid urbanization there is an urgent need for them to engage in active urban food governance, and to understand food in the context of other urban systems, such as spatial planning, urban health, education, and social services.

“We have at best 10 to 20 years before most African cities are built and the systems are cast in concrete. We don’t want to have systems with shopping malls, and ultra processed foods, and take-aways and drive-throughs everywhere. We need systems that work for different societies.”

Mutual city-to-city exchange over food governance is helpful; for example, Cape Town had a fruitful partnership with Toronto, Canada for several years. However, some challenges are specific to Africa. African food systems are characterized by a high degree of informality; stakeholders (such as food vendors) often start operating, then lobby for services and seek incorporation in the planning system later. When it comes to land, there are often traditional authorities that control access to land, alongside or in place of local government.

Experiences in Kisumu and Tunis

The agenda turned next to the current food governance situations in two AfriFOODlinks cities, Tunis (Tunisia) and Kisumu (Kenya)

Paul Opiyo, Kisumu city researcher for AfriFOODlinks, presented the food system governance system and challenges in Kisumu, and how these challenges are being addressed under AfriFOODlinks.

Agriculture and food security are the responsibility of county governments in Kenya. Thus, the Kisumu Food Strategy 2023-27 covers the whole of Kisumu County. Implementation has been hampered by institutional structures, however. Firstly, the strategy takes a city region approach but specifically urban food issues are not adequately acknowledged. Secondly, Kisumu city is the responsibility of the County Department of Physical Planning and Urban Development, which has no food mandate.

Kisumu has the multistakeholder Food Liaison Advisory Council of Kisumu (FLACK), formed under a FAO project as an informal platform. FLACK’s membership consists of government agencies, research institutions, local NGOs, development partners, private sector players, and financial institutions with an interest in the food system.

The AfriFOODlinks project in Kisumu is currently working to strengthen FLACK with the inclusion of more relevant stakeholders, such as influential civil society organisations and development partners. The team is also seeking funding to enable the FLACK to become a permanent, stable platform.

Rose Achieng, Nutrition Officer at Kisumu County, said resources would support day-to-day administrative activities of the FLACK secretariat, and coordination and collaboration between various departments and ministries, civil society, and NGOs. Resources would also enable the platform to assist in food-related policies and to play an advocacy role. Some funds would be used to strengthen monitoring and evaluation, increasing transparency and accountability.

Emma Morganui, Hivos AfriFOODlinks Coordinator for Tunis, sketched out how advances in food systems governance have been derailed by political instability, causing the AfriFOODlinks team to adapt its approach.

Although food security is a responsibility of Tunisia’s government, decentralization following the 2011 revolution and the 2014 Constitution led to the take up of food issues by local governments. In 2019, the Mayor of Tunis signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact; two years later the municipality released a draft food strategy, prepared with the technical and financial support of FAO. The strategy focused on citizen rights, efficiency, participation, and accountability. It provided for the establishment of a food desk or food security unit within the municipality and a multistakeholder platform. The strategy was to be driven by a core team charged with formulating an action plan.

However, Tunisia underwent a major political shift in 2021 and a new constitution came into force in 2022. In 2023, municipal councils were dissolved. With the champions of the food strategy process no longer in post, the process came to a halt.

In this context, the AfriFOODlinks team in Tunis is focusing on strengthening the core team, capacity building for municipal officials, adapting the strategy to ensure resilience and relevance for ongoing challenges, and research and diagnostics.

‘To move forward, we are building more solid relationships between actors working on the food system, while waiting for an end to the perpetual change in the political system,’ said Mornagui.

An international view

A discussion on the experiences of Kisumu and Tunis was facilitated by Barbara Emanuel, Chair of RUAF and former manager of the Toronto Food Strategy. The discussion touched on issues such as support from multilevel policy framing, how to secure engagement of the various local government departments with a role related to food, and tactics to ensure inclusivity and meaningful participation.

In view of the recent experiences in Tunis, Emanuel remarked: ‘It is a very common experience for cities across the world to be subjected to governance changes that are beyond their control.’

She recalled how political changes in Toronto resulted in fewer resources and less capacity for the Food Policy Council and food strategy, which had existed for over 30 years.

Andrea Patrucco, Manager of the EU-funded Food Trails programme for the city of Milan (one of the five European Sharing Cities in AfriFOODlinks), highlighted the importance of cross-learning and leveraging existing tools. For example Food Trails, which involves 10 municipalities across Europe, developed a grid to support multi-level advocacy, so cities could focus their efforts over relevant issues at the right level. Such a tool might be helpful in Africa.

‘There is a lot we can learn from each other, and so many common issues all over the world, including lack of resources and lack of legal capacity vis-à-vis local government,’ said Patrucco. ‘But there is so much we can do at the city level – and so much we can do because we are the government closest to the community. We see the impact of the pressures and policies at the local level.’

More information on AfriFOODlinks is available here.

Watch the webinar recording: