By Chibuzor Charles Ubah and Jess Halliday

Multistakeholder processes are a recognised good practice for developing food systems actions and interventions. While they bring many benefits, inherent power dynamics may influence decision-making and there is a risk of tokenism in lieu of meaningful inclusion of disempowered and marginalized stakeholders. Rikolto convened the RUAF Global Partnership on Sustainable Urban Agriculture and Food Systems to present its new resource, Facilitating multi-stakeholder processes: a toolkit, and share experiences of addressing power and inclusion in Arusha, Tanzania.

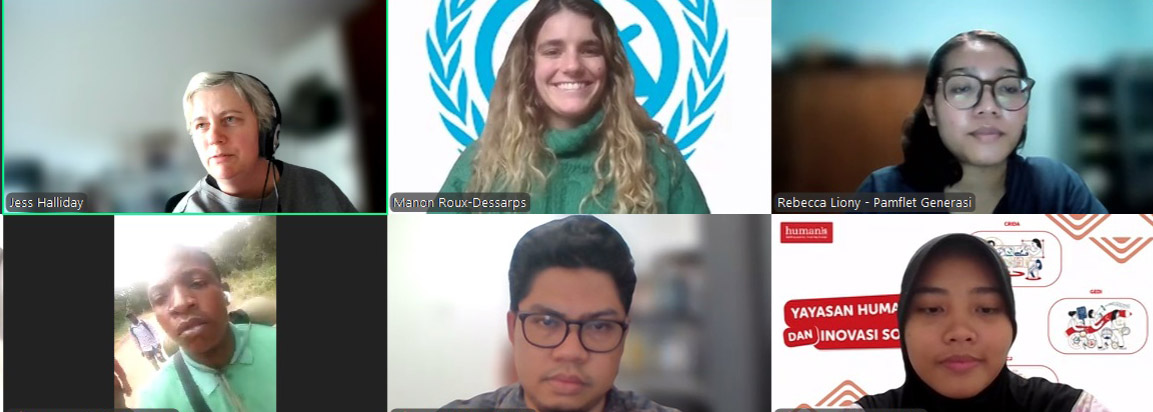

Photo by David Minja. Participants in the first meeting of 2023 of the Arusha Sustainable Food System Platform, where members discussed strategies to improve the functioning of the platform.

A multistakeholder process is a participatory mechanism that involves identification of the relevant actors needed in the discourse, recognizes the divergences in their backgrounds, knowledge, values, norms, and opinions, and creates an enabling environment for dialogue and negotiation. The stakeholders aim to reach a consensus on a shared vision based on mutual understanding. It is a governance process that brings public and private individuals and organisations into the decision-making process.

Food policy councils, food boards, food change labs, food partnerships, food policy networks, food coalitions, and working groups are examples of existing multistakeholder platforms that bring stakeholders together for inclusive and collaborative governance, exchange of ideas on challenges affecting the food system, to generate innovative solutions, and to derive policy decisions for interventions and planning.

Rikolto developed its Facilitating multistakeholder processes toolkit to highlight the necessary tools and attitudes needed to facilitate a robust multi-stakeholder process.

At the meeting of the RUAF Global Partnership, Charlotte Flechet, Global Programme Director, Good Food for Cities, at Rikolto, gave an overview of the toolkit, and explained the six building blocks of a multistakeholder working: system thinking, multistakeholder dialogue and facilitation, shared vision and collaboration, stakeholder engagement, learning and exchange, and a multistakeholder governance system.

She drew members’ attention to attitudes, tips, and innovative strategies to deal with power dynamics, tensions, and (often unconscious) bias that emerges during the multistakeholder process, and highlighted various ways of driving meaningful participation. These include the dialogic approach, divergence-emergence-convergence, iterative interaction, the whole system in the room approach, differentiation and integration, and multi-channel learning which are further described in the toolkit.

The facilitator’s role

Strong and conscious facilitation is critical to redress power imbalances between stakeholders.

The role of the facilitator is to support and marshal meetings, negotiation, and collaboration. The facilitator seeks the active participation of the stakeholders, from the marginalized to the more powerful actors, and checks power dynamics that emerge from interactions between stakeholders. They ensure that every actor has a voice and that every view is considered important.

A strong facilitator displays:

- Creativity: can think uniquely, to create and facilitate new engaging platforms where actors can be drawn into a collaborative framework towards achieving a shared vision

- Resilience: able to manage the differences that exist between the actors, prevent and settle conflicts as they arise

- Eldership: ensures that all voices are heard

- Presence: be aware of one’s own prejudice while ensuring that such behavioral tendencies do not mar the progress of the platform and engage in deep listening

Members of the RUAF Global Partnership debated the question of how to deal with one-stakeholder dominance in discussions. Rene van Veenhuizen, senior programme manager at Hivos, suggested one tactic entails dividing the stakeholders into smaller working groups to drive better communication. This can also help in situations where some stakeholders do not adequately communicate their needs, meaning their interests are at risk of being overlooked.

Others questioned whether social acceptance or training best qualifies a facilitator. Charlotte Flechet explained that Rikolto staff have technical facilitation skills but tend to play a supporting role in multistakeholder processes – while a socially-acceptable facilitator, who has a more trusting relationship with the stakeholders, drives effective participation. Nonetheless, it is important that the facilitator remains neutral.

Assessing the Arusha Sustainable Food System Platforms

Hildagard Okoth, who leads the Arusha Sustainable Food Systems Platform for Rikolto, demonstrated how the multistakeholder process has been used to address food system challenges in Arusha, Tanzania, with a particular focus on food safety in vegetable production.

Following Arusha’s signature of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact in 2015 and a city-to-city exchange with Antananarivo, Madagascar, in 2018, food safety was identified as a key entry point for food systems transformation. In particular, there was a need to reduce the exposure to pesticides to an acceptable daily intake and to reduce the level of microbial contamination. Addressing these issues would require all stakeholders in the food value chain, from production to consumption.

Consequently, the Arusha Sustainable Food Systems Platform was formed in 2020, with members representing government, consumers, informal market workers, market vendors, transport unions, city planners and logistics, and also the youth who are strong agents of mobilization. Coordination is provided by Rikolto, but the intention is that Arusha City Council take on the role of co-chair or co-coordinator. The platform has five thematic working groups – consumer sensitisation, food safety standards, safe production, youth in agriculture, and city planning and logistics. Each working group has a sub-lead who is both trained to work with power dynamics and who is socially acceptable.

Among its successes, the platform had been able to organize and deliver trainings on safe production, link food producers to urban markets, sensitize consumers through radio shows, develop a participatory food safety scheme that connects local farms to ensure compliance with food safety standards, mobilize and empower active youth participation in agri-food business and food system discourses, organize biodiversity campaigns on tree perennial tree plantings, and promote investment in the circular economy.

In 2022, Rikolto decided to evaluate the Platform’s functioning. The assessment tool covered the six building blocks of multistakeholder partnerships that are set out in the toolkit, and was administered via a survey to all members. The survey included both quantitative and qualitative questions.

Members of the MSP then reflected on and discussed the results.

The assessment highlighted the following:

- Stakeholders shared a strong vision of tackling the food system challenges. However, there was no clear framework to tailor decisions. This also resulted in a deficit in translating the visions into workable plan.

- Indicators to measure the performance of the process were lacking.

- There was a need for continued exploration of the food system, to identify emerging challenges and trends and enable the creation of innovative solutions.

- The ineffective or zero participation of some stakeholders in the process remained a problem. Key actors were not fully represented, so there was a need to diversify the membership of the platform to include more private sector, media, consumer, and informal workers representation.

- The stakeholders who participated were constrained by a lack of understanding of food system jargon.

- Lack of financial capacity was also a setback, as stakeholders funded the MSP through personal or organizational contributions. Hence the need to develop strategies for raising funds.

- To ensure efficiency in the functioning of the platform and its sustainability, members suggested having a socially acceptable actor, together with a technically-capable actor, to coordinate the platform. This became one of the driving factors that pushed the twenty stakeholders in the Arusha sustainable food systems platform to advocate for the adoption of the Arusha city council as co-coordinators.

The members developed a concrete action plan to address these issues, and to measure progress and generate an evidence base around the effectiveness of the multistakeholder process.

‘The experience in Arusha demonstrates that setting up and running a multistakeholder platform is not a one-off,’ said Jess Halliday, chief executive of RUAF.

‘It really shows the importance of checking in every now and then on how it is functioning – whether the right people are present and able to participate, whether there are any barriers to participation, whether information is accessible and understandable, and whether the platform is equipped to identify emerging issues and monitor progress.’

Chibuzor Charles Ubah is an intern at Rikolto