Author: Sam Ikua, Mazingira Institute

The COVID-19 crisis has disrupted urban rural linkages, posing unprecedented challenges to cities and their systems. City lockdowns have affected the flow of people and goods into and out of cities. This disruption has created food shortages, putting a majority of the urban population at risk of being food insecure. We previously reported on the impact of these challenges in a series of video diaries from food system actors in Nairobi.

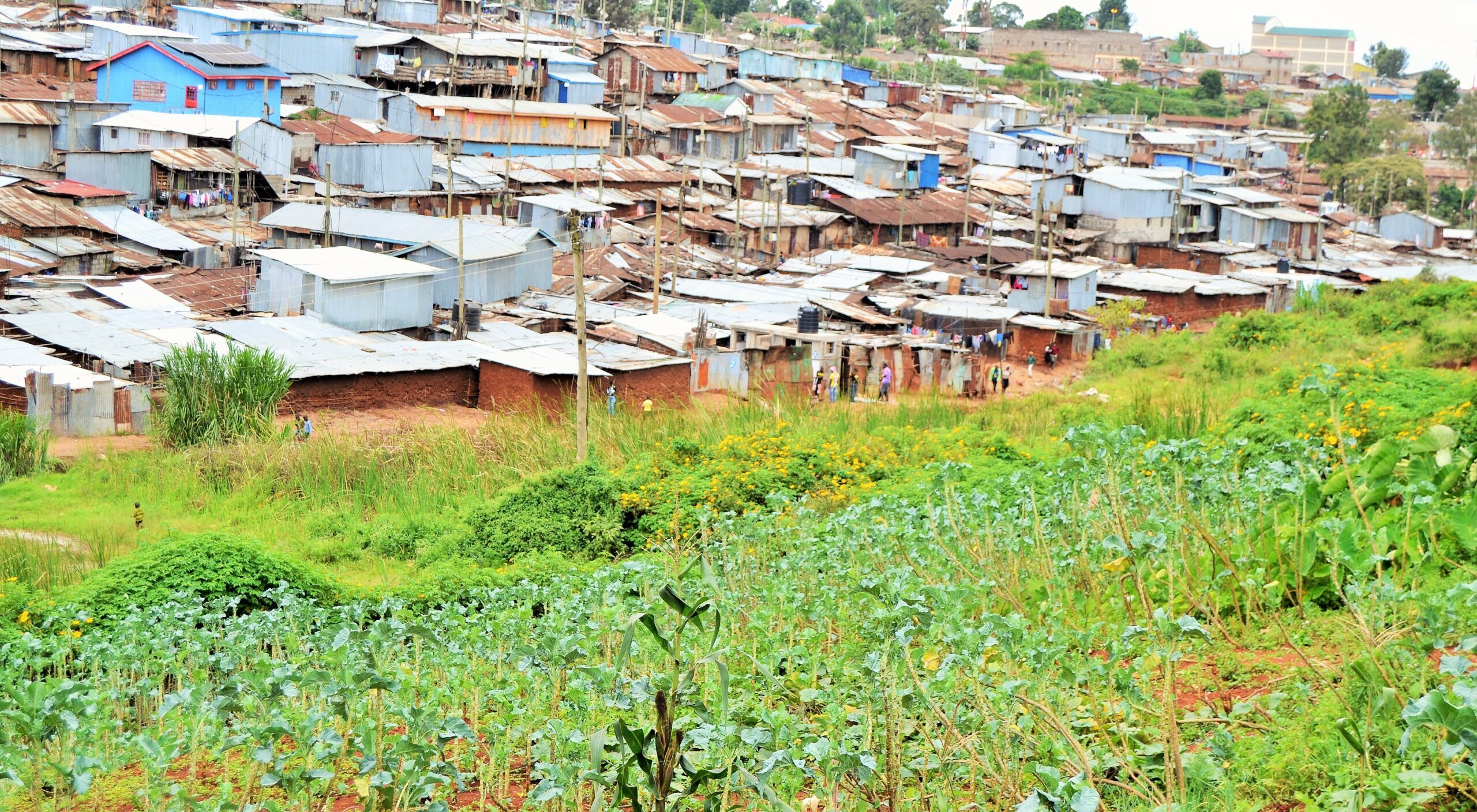

However, there is no doubt of urban agriculture’s effectiveness as an intervention to food insecurity in cities. For Nairobi, this has been demonstrated by the significant number of residents relying on urban agriculture for regular supply of food, following the cessation of movement into and out of Nairobi. From keeping dairy goats in the backyard and producing vegetables in public spaces, to rearing chickens along a shared corridor between houses in informal settlements, all these actors are contributing food to the Nairobi food basket.

A systems approach to urban agriculture

These activities have been made possible through both institutional and legal support. In terms of institutional support, Nairobi has a Food Systems Directorate within its Food and Agriculture Sector. Using a systems approach to urban agriculture, rather than acting as disjointed independent sectors, has created effective synergies among key stakeholders in the sector. Producers coordinate with processors who then give their products to distributors for sale, while waste managers recycle waste which is then used as inputs by producers. An example of this is organic vegetable producers using compost as manure. In addition, Nairobi has an agriculture extension officer in every sub-county. These officers are always available for phone consultations and regularly visit farmers on the farm for guidance on technical issues.

For legal support, Nairobi has the Urban Agriculture Promotion and Regulation Act (2015), which mandates the authorities to provide water and space for food production in informal settlements. These support systems have created a conducive environment for the practice of urban agriculture and allow it to continue thriving.

Urban agriculture in action

Jemimah, 44, produces vegetables in Kibera, Africa’s largest slum. She acknowledged that her sales have increased during the current crisis, saying “I now have a high number of customers because there are not many vegetables available in the market from upcountry nowadays”. As people are not allowed to travel, they now buy from her farm which is in the neighbourhood. Jemimah attributes her continued production, despite the cessation of movement, to local access of inputs. She gets manure from livestock keepers in her area and seeds from local agro-vets. She also plants vegetables in different stages, noting that, “when I finish harvesting some, there are others already mature for harvesting and others are ready for planting”. This keeps the production constant.

With many people preferring to stay at home, David, 55, a dairy cattle producer, has also experienced an increase in customers. He attributes this to his home delivery services, as people do not want to go out for shopping. The lack of movement in Nairobi has not affected his access to inputs since he sources them locally.

Joyce, 40, rears indigenous chickens for eggs. As she feeds them kitchen waste and vegetable cuttings from the farm, they are not costly to maintain and she has been able to continue production as normal. Joyce says, “my production cost is low, hence I have not increased the price even though there is shortage of eggs in the market”. Similarly, her sales have not been affected because many customers are within the neighbourhood and they just walk to the farm.

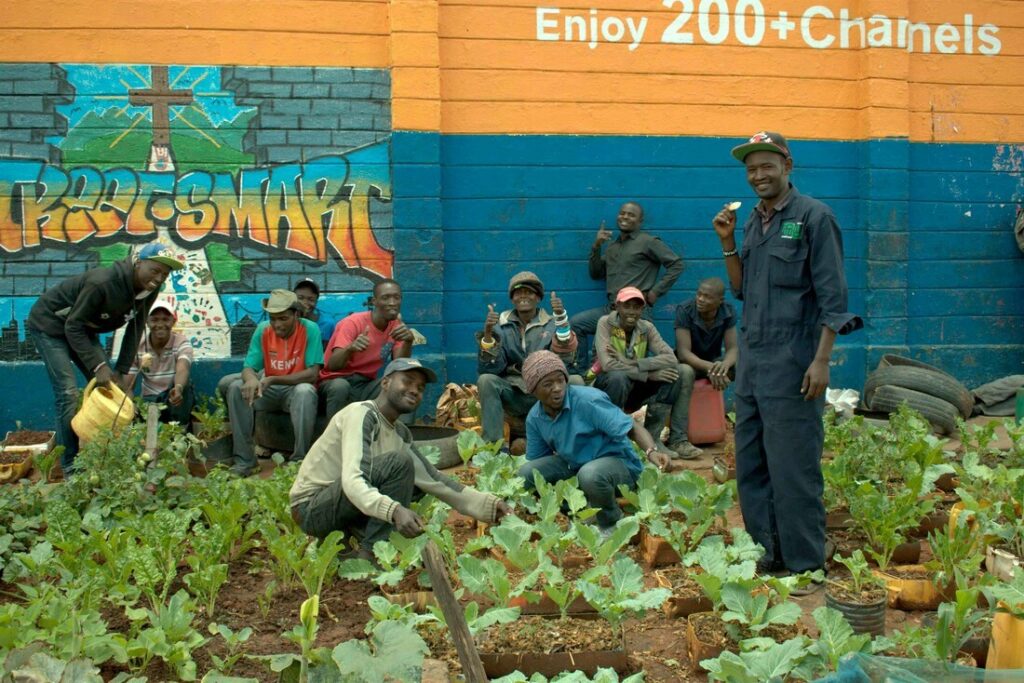

In another part of the city, a group of 35 youth, some of them homeless, grow vegetables and herbs in a public space. Since the space is limited, they use urban agriculture technologies such as container and sack gardening. They farm for subsistence and income, using the money to buy maize flour to cook a meal of ugali. In a time when regular food supply is not assured, urban agriculture has proved to be an effective intervention against food insecurity for the group and their neighbours. They are still selling to community members and they say their sales have not been affected by the current crisis. Stephen, a member of the group, says, “Our customers are still coming. They like our products because they are organic”. Just like other small-scale farmers, they get manure from the neighbours and seeds from local agro-vets. The cessation of movement has not affected their production as they access all their inputs locally.

Lessons from the crisis

Two lessons from the urban agriculture experience in Nairobi stand out: the importance of a localised food system and short food supply chains. According to the Community Wealth Organisation, a localised food system integrates sustainable food production, processing, distribution, consumption and waste management. This enhances the environmental, economic and social well-being of that particular area.

Approaching food production through a localised food system, vegetable producers have been getting manure from livestock producers within the local area, while livestock producers buy feed from local agro-vets and fodder crops from their neighbours. Despite the disruption of supply chains, local access to inputs has made it possible for the farmers to continue with production. A localised food system is also more attractive to consumers. This is because small-scale farmers are highly likely to practice organic farming, hence producing safe food. The farmers’ first priority is subsistence, with selling being secondary. Thus they have a higher incentive to produce safe food because they are the first consumers. This system is beneficial to both the producers and consumers; consumers access safe and fresh produce with ease and the farmers are assured of a regular market.

The effectiveness of short food supply chains has also been demonstrated through their resilience in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis. With some food markets closed and mama mbogas (women vegetable vendors) out of business, consumers have been buying vegetables directly from the farm. The direct producer–consumer marketing channel has made it possible for consumers to easily access safe and affordable food. The food is not exposed to unhygienic conditions through unsafe handling by middlemen and the price is low as there is no transportation and other logistical costs involved.

The future of food security

While the COVID-19 crisis has challenged the existing systems, it has shown us that localised food systems and short food supply chains are the future of food secure communities. Furthermore, urban agriculture has demonstrated its capacity to address food insecurity in cities and we should therefore encourage the practice of it. This presents an opportunity for policy makers to design and implement urban agriculture policies that support localised food systems and short food supply chains.

This work has been made possible with funding from the CGIAR Research Programme Water Land and Ecosystems, led by IWMI.