By Akiko Iida – project lecturer at the School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo – and Makoto Yokohari – presidential endowed chair of ARISE City Research Unit, The University of Tokyo.

Urban-rural mixed landscapes in Tokyo offer a rare and inspiring example of how a dense metropolis can sustain its agricultural heritage. Once dismissed as a consequence of unplanned urban sprawl during the postwar period, these landscapes are now recognized as a sustainable urban form. This article introduces the concept of “urban satoyama” – a contemporary interpretation of traditional satoyama landscapes within the urban context – and draws on historical transitions and current practices to examine how it supports evolving circular food systems.

Urban agriculture in Tokyo, Japan, has a history spanning over 400 years. In 1603, when Tokugawa Shogun established Edo (present-day Tokyo) as the new capital, agricultural villages developed in the peri-urban and rural areas to supply fresh food and fuel to the growing city.

Even after the fall of the Edo Shogunate and Japan’s subsequent opening to the outside world in 1867, the landscapes of peri-urban and rural areas remained largely unchanged. However, following World War II Tokyo experienced rapid urban sprawl, leading to widespread urbanization and a significant reduction in farmland and woodlands.

In response, the Productive Green Land Act was revised in 1991 to help conserve urban farmland (see Box by downloading the full issue). According to the census in 2020, approximately 10 000 farming households and 6530 hectares of farmland remain in Tokyo, accounting for 0.1 percent of all households and 3 percent of the city’s land, respectively. It contributes to Tokyo’s distinctive urban–rural mixed landscape.

These mixed-use urban areas were formed as a result of the interaction between two opposing forces: agricultural stakeholders who aimed to preserve farmland and urban planners who sought to promote urbanization in response to housing shortages. From the perspective of those advocating urbanization, the lack of a clear boundary between urban and rural areas, as well as the presence of urban farmlands within high-dense urban areas, was sometime regarded as a failure of urban planning.

However, as Japan entered an era of population decline in 2008, a major shift in perspective occurred. In 2015, the Basic Act on the Promotion of Urban Agriculture was enacted, marking a significant turning point in national policy. In 2017, the City Planning Act was also amended, introducing a new land-use zone called Garden Residential Zone (Den’en Jūkyo Chiiki), specifically intended to preserve farmland within residential areas. Today, even from urban planners’ standpoint, urban farmland is recognized as an integral and valuable land use within cities.

The origins of satoyama

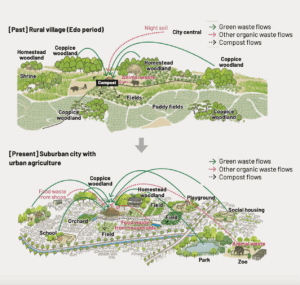

In the Kanto Plain, where Tokyo is located, much of the soil is Kanto Loam. Formed from volcanic ash, it holds water well but tends to drain poorly and is typically low in nutrients. To improve soil quality, agricultural woodlands were developed as a traditional form of land use during the Edo period. Farmers collected leaf litter to produce organic compost and improve soil fertility. They also used various types of organic waste – including grass ash, animal manure and human night soil – as fertilizers. By the early 18th century, Edo had grown into a metropolis of over one million people, supported by circular agricultural practices.

At that time, rural villages were composed not only of rice paddies and vegetable fields, but also of diverse landscape elements that formed unique socio-ecological productive landscapes known as satoyama. These included homestead woodlands (yashikirin) that surrounded farmhouses, coppice forests (zoukibayashi) used to collect leaf litter and firewood, agricultural irrigation channels, drinking water channels, and rivers.

Over time, however, these satoyama landscapes became fragmented due to urban sprawl. Contaminated water led to the termination of rice paddies, while the widespread use of chemical fertilizers and gas diminished the need for coppice forests. Many fields were also converted into residential areas. What remains today are urban farmlands maintained by farming households, the homestead woodlands (yashikirin), water channels with recycled water from sewage treatment plants and rivers that have been entirely concreted.

Evolution in urban context

Although these transformed landscapes may seem to have lost the beauty and integrity of traditional satoyama, the underlying systems of resource use have not disappeared. They have evolved and adapted to urban realities.

For example, rather than collecting leaves from coppice forests, today’s farmers gather leaf litter from shared green spaces within the urban fabric, such as urban parks, schoolyards, roadside trees and shrines. Some urban farmers also utilize food waste such as rice bran or buckwheat husks from nearby stores, and even manure or bedding straw from zoos.

In many cases, such practices have been carried out based on farmers’ own decisions rather than as the result of institutional support from local governments. The farmers cite economic reasons, such as the lower cost of producing their own fertilizer from freely available organic waste instead of purchasing chemical fertilizers, and operational reasons such as the need for organic compost to create high-quality soil.

This evolving system could be described as a modernized “urban satoyama”, a contemporary form of socio-ecological landscape that reinterprets traditional resource circulation within the urban context. Unlike traditional satoyama, urban satoyama landscapes incorporate green waste from urban parks and organic waste generated by urban residents to support circular agricultural practices.

Of course, not all urban farmers follow these traditional practices; many have shifted entirely to chemical fertilizers. However, in addition to older generations, younger urban farmers with a strong environmental consciousness are increasingly adopting organic farming method inspired by the traditional circular practices of satoyama agriculture, including leaf compost farming.

Urban circular food systems

Today, farmers are leveraging their proximity to residential areas to operate their agricultural businesses in various ways. One such approach is direct-to-consumer sales at farm stands, in which more than 70 percent of Tokyo’s urban farmers engage. Others supply produce for school lunches, or lease plots for allotments and community gardening. These diverse strategies take advantage of the urban-rural mixed landscape and represent a distinctly urban characteristic. They differ from rural farming, which primarily focuses on wholesale market distribution.

This proximity allows Tokyo’s urban farmers to keep the distance between production and consumption remarkably short. Residents can enjoy locally grown produce while passing by the very fields where it was cultivated. This proved to be a significant advantage during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to restrictions on movement, global supply chain disruptions drew increased attention to local food sources such as farm stands and allotments. Recent research found that urban residents in Tokyo who used farm stands or allotments had significantly lower levels of concern about current and future food insecurity than those who did not. This underscores the critical role of local urban food systems in ensuring food security and community resilience in times of disruption.

Moreover, Tokyo’s local food system involves not only production and consumption but also the reuse of organic waste through composting. This small-scale, closed-loop model supports urban sustainability by reducing waste, conserving resources and reintegrating nutrient cycles within the city.

Tangible and intangible heritage

The urban-rural mixed landscapes of urban satoyama in Tokyo represent a form of tangible cultural heritage that is continuously evolving. Equally important is the continuity of intangible heritage, including traditional farming practices such as leaf composting and the knowledge of cultivating heirloom crops. These tangible and intangible forms of urban satoyama have been shaped through the collaborative efforts of individual farmers, agricultural cooperatives and government bodies responsible for creating supportive policies.

Going forward, it will be essential to further evolve tangible and intangible heritage by actively engaging citizens in this process. This would not only support the ageing population of urban farmers, but also provide urban residents with a meaningful way to reconnect the wisdom of satoyama with urban life. Such engagement could inspire shifts toward more circular lifestyles among citizens. This, in turn, embodies the contemporary value of urban satoyama as a living heritage.

Download the full issue of Urban Agriculture Magazine 42 below to explore the whole article.